Mismatched Puzzles: Navigating the Design Skill Maze

Assigning the Right Problems to the Right Design Skills

Every designer can recall the twists and turns of their first challenging project. Where the stakes were as high as the learning curve. At times, these challenges have a way of leaving us feeling completely overwhelmed. On other occasions, we find ourselves in a realm where our skills are underutilized, the thrill of challenge evaporating into the mundane routine of predictable tasks.

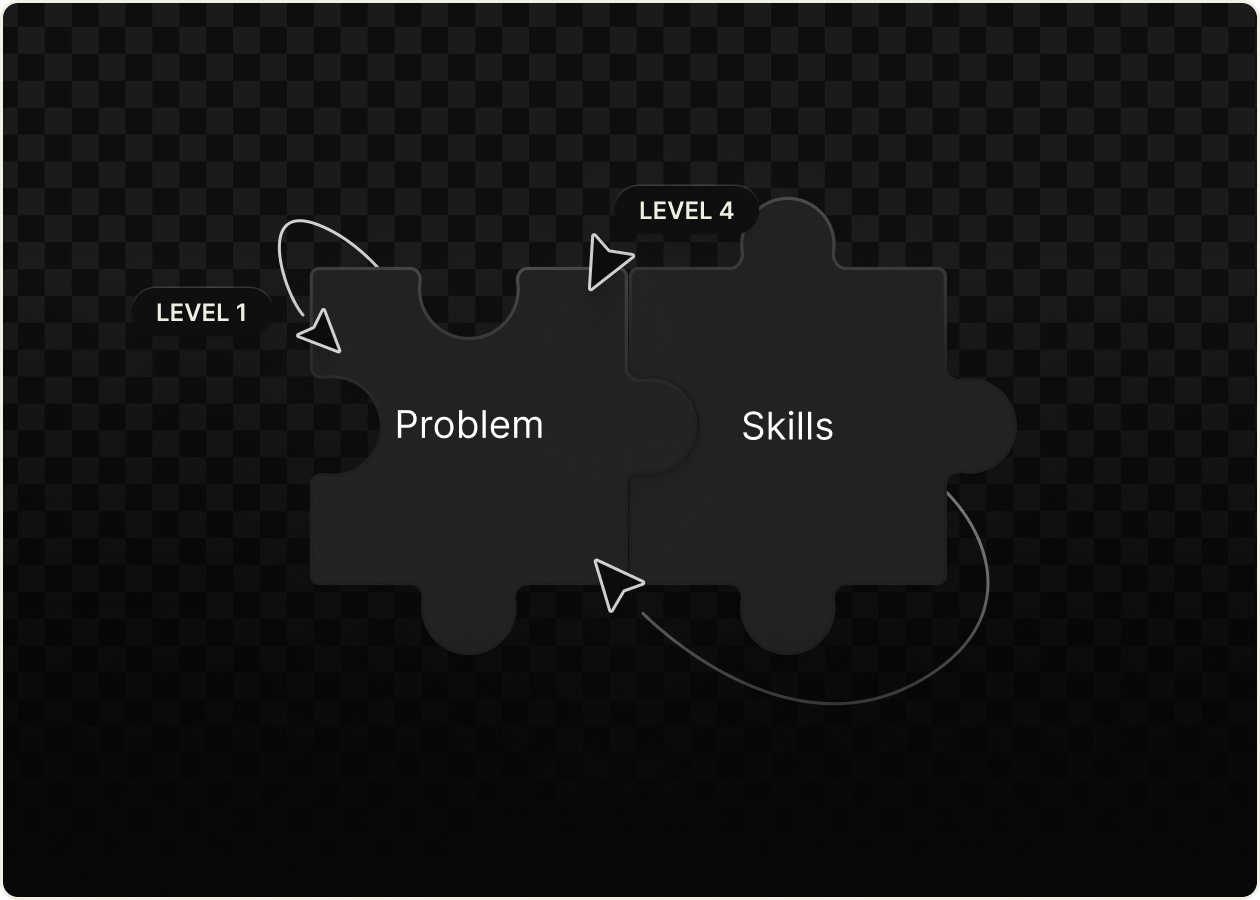

At the heart of these scenarios lies a common antagonist: the 'Design Problem Skill Fit.' Often companies and organizations stumble when it comes to aligning the problems their product, service, or company faces with the design skills they have available to solve them.

Understanding Design Skills

Designers are problem solvers at heart. Understanding the breadth of design skills they bring to the table is the first step toward ensuring a harmonious alignment:

User Research: Finds what problem to solve for your (potential) users.

Who are we solving the problem for? What exactly is the problem? How do we know the problem is real?

Interaction Design: Explores all possible solutions that fit with (potential) users and commits to one. Defines how the solution should work.

What are potential solutions for solving the problem and how should they work?

Visual Design: Defines how the solution looks and feels.

Does the solution convey the message effectively, maintain visual/system consistency, and evoke desired emotions?

Product Design: Ensures that the solution creates and captures value for (potential) users and the business.

Is the solution effective in solving the problem, useful to people, and aligned with product strategy and business objectives?

The spectrum of design skills required varies across companies and their products, with each designer often showcasing pronounced strengths in specific disciplines. While larger design teams are able to afford the luxury of individual specialization having individual designers proficient in all design disciplines tends to yield far superior quality products and experiences. Great user research, robust product strategy, intuitive interactions, and compelling visuals are not mutually exclusive domains — they are interdependent facets of a singular craft. Mastering all these disciplines is possible; it just takes time and effort — after all design is a craft.

Being skilled in user research and interaction design is valuable, but lacking in visual design could put you at a disadvantage as soon as someone shows up that can handle all three. Similarly, focusing solely on the aesthetic aspects of design, without addressing the relevant problems or developing functionality that resonates with (potential) users, is a misguided approach. Such a narrow focus on visual design, detached from the actual needs and preferences of users, is unlikely to drive success for either the designer or the company. Mastery in each discipline is a journey, not a race— this is what shapes a design career.

This evolution of skill naturally leads to a critical question: As designers progress and refine their abilities in user research, interaction design, visual design, and product design, what distinguishes a junior from a senior designer? Beyond speed and efficiency, how do their challenges and responsibilities differ?

Understanding Design Levels

The more senior the designer, the more abstract the problems they should be tackling.

Julie Zhou’s framework, although a decade old, provides a lens to view the evolution of a designer. As designers climb the ladder, the problems they tackle morph from concrete to abstract, demanding a broader perspective and strategic insight.

Designer Level 1: Design a sign-up form that allows people to easily create an account.

Includes creating a form, considering fields and information that makes sense for someone to create an account.

Which fields are absolutely necessary?

What's the most efficient layout for the sign-up form?

Designer Level 2: Design the sign-up experience to minimize user drop-of.

Possibilities could include streamlining the sign-up into a three-step process, requiring only minimal upfront input initially, or perhaps introducing social sign-up options.

From where are users being directed, and what is their context before they engage in the sign-up process?

Where are the current drop-off points and why?

How can we make the sign-up as effortless as possible?

Designer Level 3 (deep): Design a solution that will help users understand your product's value and convince them to sign up. Identify the optimal moment for sign-up, that aligns with a user's realization of the product's benefits, demanding a deep comprehension of user motivation and behavioral design.

What compelling reasons drive users to sign up?

At what point should they be asked to sign up?

How can we showcase the value before they sign up?

Designer Level 3 (broad): Design a system that effectively onboards any user across all products. Move beyond just signing up, and think of it as a part of a larger onboarding journey. This needs a flexible system that can adjust the steps based on who's using it (buyer or seller, driver or rider etc.) and what product they're using.

How can the experience adapt to different user types and their needs?

What parts of the experience can be standardized and what need to be flexible?

Designer Level 4: Figure out what's not working with the ‘first mile’ of your product and design solution. Rather than just re-designing the sign-up process, consider if the real issue is users not grasping the product's value quickly enough. Letting users engage with the product and see its value before signing up could boost sign-ups and keep users around longer.

What barriers exist in the first interactions with the product?

When do users realize the product's value?

How can we bring the moment of value realization closer to the user's initial interaction to increase retention?

Designer Level 5: Find the biggest unknown problem with your product and design a solution. Use thorough knowledge of the product to find and address big, non-obvious challenges. At this level, the designer must have a comprehensive understanding of both the user needs and business goals to help drive the product strategy through design.

What methods will help us uncover the hidden problems?

Which problems, when solved, would yield the highest leverage in improving your product or company?

How do these findings align with our strategic objectives?

Balancing Craft and Communication Skills

As designers climb through the ranks, the complexity of problems they face necessitates a balance between their craft and communication skills. While honing craft skills remains fundamental, mastering communication and storytelling emerges as a force multiplier. With each ascending level, the imperative for effective communication intensifies. It transcends merely crafting or conveying ideas to fostering understanding, facilitating collaboration across multidisciplinary teams, and influencing cross-functional partners. Each problem tackled calls for a distinct blend and application of craft and communication skills.

Understanding Problems

What renders a design problem ambiguous? Discerning the ambiguity of a problem can be a tall order. A practical framework involves correlating designer levels to problem areas. Although reality is more intricate than a simple matrix, this methodology has steered me clear of misaligning problems and design skills. When the problem is crystal clear, the scope is well-defined. On the flip side, if you don't know where to start, higher-level design skills are likely needed to delineate the problem initially. The degree of ambiguity in scope and the associated risk level should guide the alignment of suitable design skills with the problem at hand.

Matching Design Levels to Problems

Scenario: Navigating Uncharted Waters

When a Level 1 designer faces an overly ambiguous challenge, they're stepping into scenarios reminiscent of the initial overwhelming project I mentioned in the beginning. The stakes are high and the complexity of the problem is akin to a steep learning curve, demanding a skill set and experience beyond their current toolkit. These designers are adept at tackling specific, scoped tasks, but here the problem requires a grasp of complex systems or user psychology, as well as strategic thinking. The likely outcome? They'll feel overwhelmed, leading to oversimplified solutions that don’t address the core issue. While it can serve as a stretch opportunity and a steep learning curve, without the right support, this misallocation could result in a solution that merely scratches the surface and overlooks strategic opportunities.

Scenario: Untapped Potential

On the other hand, when a Level 4 designer is tasked with a junior-level task — like 'design a sign-up flow' — it resembles the situations where skills are underutilized. There's a significant risk of dissonance if the designer believes the task at hand is misaligned with the product’s current needs or user goals. These designers have the insight to assess and question the strategy underpinning a product; if they conclude that a sign-up flow is not the optimal solution or the right focus, they may feel their talents are being wasted. This can lead to discontent and a lackluster performance as they are compelled to work on a task that does not engage their strategic skill set. The resulting tension can be detrimental to morale, particularly when a senior designer's broader vision for the product is sidelined, which, in turn, can influence the overall team dynamic and productivity.

Scenario: The Hiring Conundrum

Companies vary in how they organize the responsibilities and capabilities of designers, often shaped by their organizational maturity and design literacy. For instance, a level 3 designer might be titled a "senior designer" in some settings, while others might reserve this title for level 4 or 5 designers. The titles are secondary; what holds paramount significance is the nature of the problem at hand and aligning it with the right level of design skills. Some designers, early in their career, exhibit level 4 or 5 capabilities. Conversely, a designer with a decade of experience might excel in tackling well-defined level 1 or 2 problems but may fall short if the problem demands a higher-level perspective. When hiring seasoned designers, a more reliable indicator for a successful hire is evaluating the past problems they've solved in relation to the challenges your organization faces today, rather than merely relying on their design titles.

Exiting the Comfort Zone

For Designers: Mastering the foundational levels of design is a comfort zone for many designers, showcasing exceptional skills at levels 1 and 2. While a strong foundation is crucial, pushing beyond this comfort zone is equally essential. Often, designers may feel sidelined or overruled, leading to a notion that the organization undervalues design. However, this is just a symptom. The real issue may lie in designers not pushing their boundaries to address bigger, more complex challenges. Take a moment to consider this: are you stretching yourself but focusing on the wrong problems? It's important to emphasize that this doesn't mean these designers aren't hard working. In fact, many are putting in considerable effort, but their focus is misdirected towards lower-level issues — essentially, the wrong problems.

By taking the initiative to address higher-level issues that are crucial to both the product and the business, you not only enhance your design skills but also elevate your demand, both within your organization and in the broader industry. It's time to level up!

For Design Management: I used to think of design management as a triad of people, process, and purpose. Over time, I've come to understand that it's also profoundly about pinpointing the right problems. It's our role to discern what challenges are worth tackling within an organization and granting our teams the keys to these challenges. In doing so, we transform the essence of design management into a driving force for growth and discovery. It's about building bridges between designers and the broader goals of the organization, and then crucially, providing access to problems that keep us from achieving those goals.

Yes, it's still about nurturing talent, building culture, refining processes, and creating a sense of purpose, but it's equally about curating problems — choosing the right ones that stretch the right level of designers. Providing support and resources to venture into these unexplored territories is crucial for expanding the design management mandate.

By granting access to the most significant challenges, we pivot the conversation from constantly justifying what Design IS to showcasing what Design DOES. Only then, design is not just seen, but deeply understood and valued.